Discover the key differences between the income statement vs cash flow statement, essential financial tools for assessing a company’s profitability and liquidity. Learn how they connect and why both are vital for a complete financial analysis.

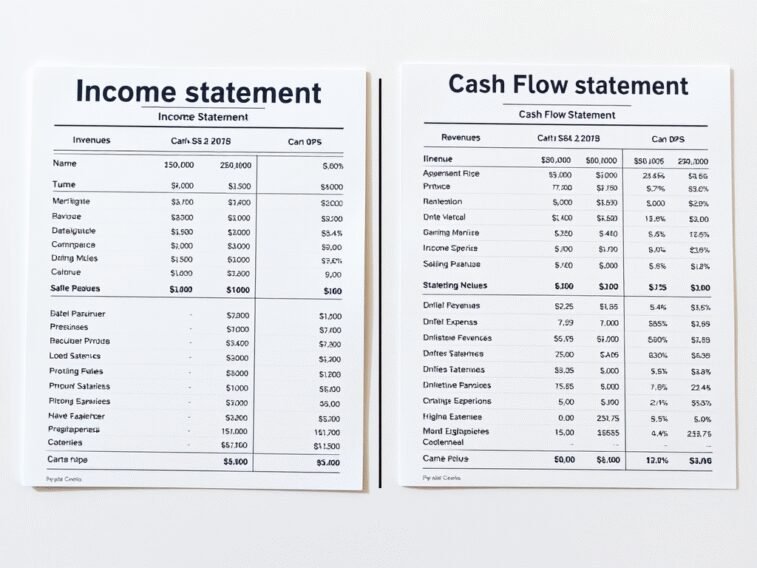

Income Statement vs Cash Flow Statement: Understanding the Key Differences

Financial statements are vital tools for understanding a company’s financial performance and stability. Two of the most critical statements are the income statement and the cash flow statement. While they both provide insights into a company’s operations, they serve distinct purposes and reveal different aspects of financial health. This article explores the differences between the income statement and cash flow statement, their components, how they’re used, and why both are essential for a complete financial picture.

What Is an Income Statement?

The income statement, often called the profit and loss statement (P&L), tracks a company’s revenues, expenses, and resulting profits or losses over a specific period—typically a quarter or year. Its main goal is to show profitability, highlighting how well a company generates earnings from its core activities.

Key Components of an Income Statement

- Revenues: Income from sales of goods or services.

- Cost of Goods Sold (COGS): Direct costs tied to producing those goods or services.

- Gross Profit: Revenues minus COGS, showing profit before operating costs.

- Operating Expenses: Overhead costs like rent, utilities, and payroll.

- Operating Income: Gross profit minus operating expenses, reflecting core business profitability.

- Net Income: The bottom line after subtracting taxes, interest, and other expenses from operating income.

Analyzing the Income Statement

Analysts use ratios to evaluate performance:

- Gross Margin: (Gross Profit / Revenue) × 100—measures production efficiency.

- Operating Margin: (Operating Income / Revenue) × 100—gauges operational profitability.

- Net Profit Margin: (Net Income / Revenue) × 100—shows overall profitability.

The income statement is key for assessing how effectively a company turns revenue into profit.

What Is a Cash Flow Statement?

The cash flow statement records the actual cash moving in and out of a company over a period. It focuses on liquidity—how much cash is available to pay bills, invest, or cover debts—rather than profitability.

Key Components of a Cash Flow Statement

It’s divided into three sections:

- Operating Activities: Cash from everyday business, like customer payments or supplier costs.

- Investing Activities: Cash spent on or gained from assets, such as buying equipment or selling property.

- Financing Activities: Cash related to funding, like loans, stock issuance, or dividend payments.

Analyzing the Cash Flow Statement

A critical metric is free cash flow (FCF): FCF = Cash from Operating Activities – Capital Expenditures FCF shows how much cash remains for discretionary use after maintaining or expanding operations. The cash flow statement reveals a company’s ability to stay liquid and solvent.

Key Differences Between the Two Statements

The income statement and cash flow statement differ in purpose, focus, and methodology:

| Feature | Income Statement | Cash Flow Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Measures profitability | Tracks cash movement |

| Accounting Basis | Accrual (revenues/expenses when earned/incurred) | Cash (actual cash transactions) |

| Focus | Earnings and costs | Liquidity and cash availability |

| Non-Cash Items | Includes depreciation, amortization | Excludes non-cash items |

| Time Perspective | Performance over a period | Cash position during a period |

Real-World Example

Imagine a company earns $15,000 from credit sales. The income statement records this as revenue, boosting net income. But since the cash hasn’t been collected, the cash flow statement shows no inflow. Conversely, a cash-rich company might show a loss due to high depreciation—a non-cash expense—while still having positive cash flow.

How They Connect

The two statements aren’t isolated—they’re linked. The net income from the income statement kicks off the operating activities section of the cash flow statement. Adjustments then account for:

- Non-cash items (e.g., adding back depreciation).

- Working capital changes (e.g., subtracting increases in receivables).

For instance:

- Net Income: $30,000

- Depreciation: $10,000

- Increase in Receivables: $5,000

[ \text{Cash from Operations} = $30,000 + $10,000 – $5,000 = $35,000 ]

This connection ties profitability to cash generation.

Why Both Matter in Financial Analysis

Together, these statements offer a fuller picture:

- Income Statement: Highlights profitability and efficiency—ideal for spotting growth trends.

- Cash Flow Statement: Shows cash health—crucial for assessing short-term viability.

Practical Scenario

A tech startup reports $50,000 in profit but spends $70,000 on new servers. The income statement looks strong, but the cash flow statement reveals a cash deficit, signaling potential trouble if sales slow.

Warning Signs

- Profits without cash: Could mean uncollected receivables or accounting tricks.

- Cash without profits: Might reflect temporary boosts (e.g., loans) masking poor operations.

Reconciling the two helps uncover risks or opportunities.

Conclusion: Two Lenses, One Picture

The income statement and cash flow statement are complementary tools. The income statement tells the story of profitability—how well a company earns. The cash flow statement reveals liquidity—how well it manages cash. Alone, each is incomplete; together, they provide the clarity needed for smart financial decisions. Whether you’re an investor, manager, or analyst, understanding both ensures you see the full financial narrative.